In Central St. Gilles, by Renzo Piano building workshop, the building is carved to allow sun through into the courtyard at midday throughout the year, precisely the time when people gather for lunch.

1. Introduction

Designing a space involves understanding its intended activity and the time it occurs. Flexibility of course is crucial as spaces may host various activities and times. However, we can begin with a general idea, considering climate conditions to see what is available. Then we can align designs to leverage these natural elements, reducing energy consumption and enhancing comfort.

For instance, lunch typically happens between 12:00 and 14:00. Recognizing common mealtime patterns allows us to optimize spaces accordingly. Providing sun exposure during lunch identified lunch hours enables individuals to choose shade, enhancing the overall quality of the space. Allowing these options, whenever possible greatly improves the overall quality of the space. This thoughtful approach promotes sustainability and user well-being.

2. Time frames and daylight - An example

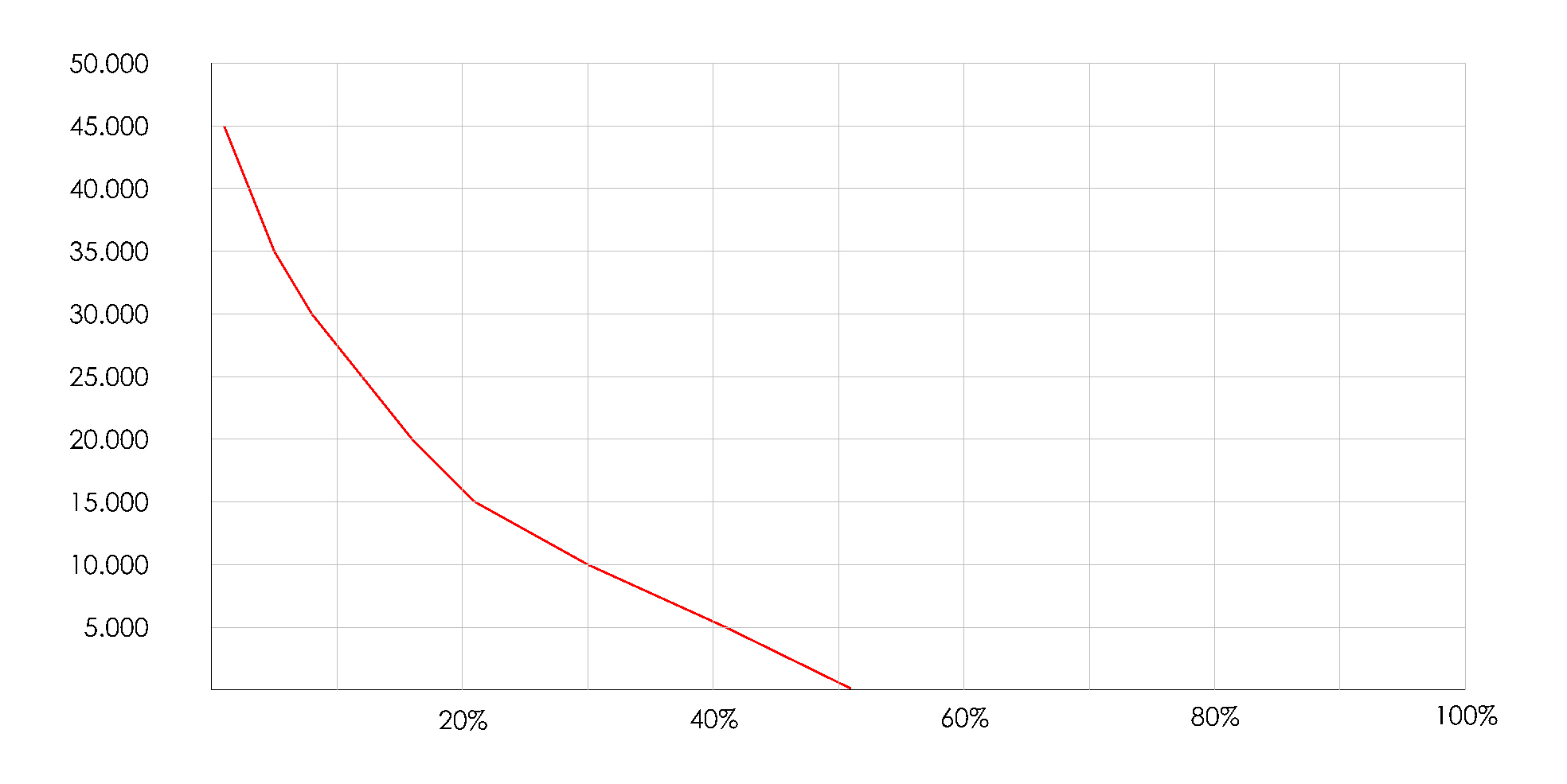

In the initial stages of the design process, time frames play a crucial role in managing expectations. Consider designing a classroom aiming for a consistent 500 lux illumination. Acknowledging the limitations within the Belgian climate, we recognize that achieving this solely through natural means 100% of the time is impossible. Consequently, we establish a benchmark. Informed by this, we define the design goal to meet the requirement naturally for 75% of the time, ensuring a realistic objective.

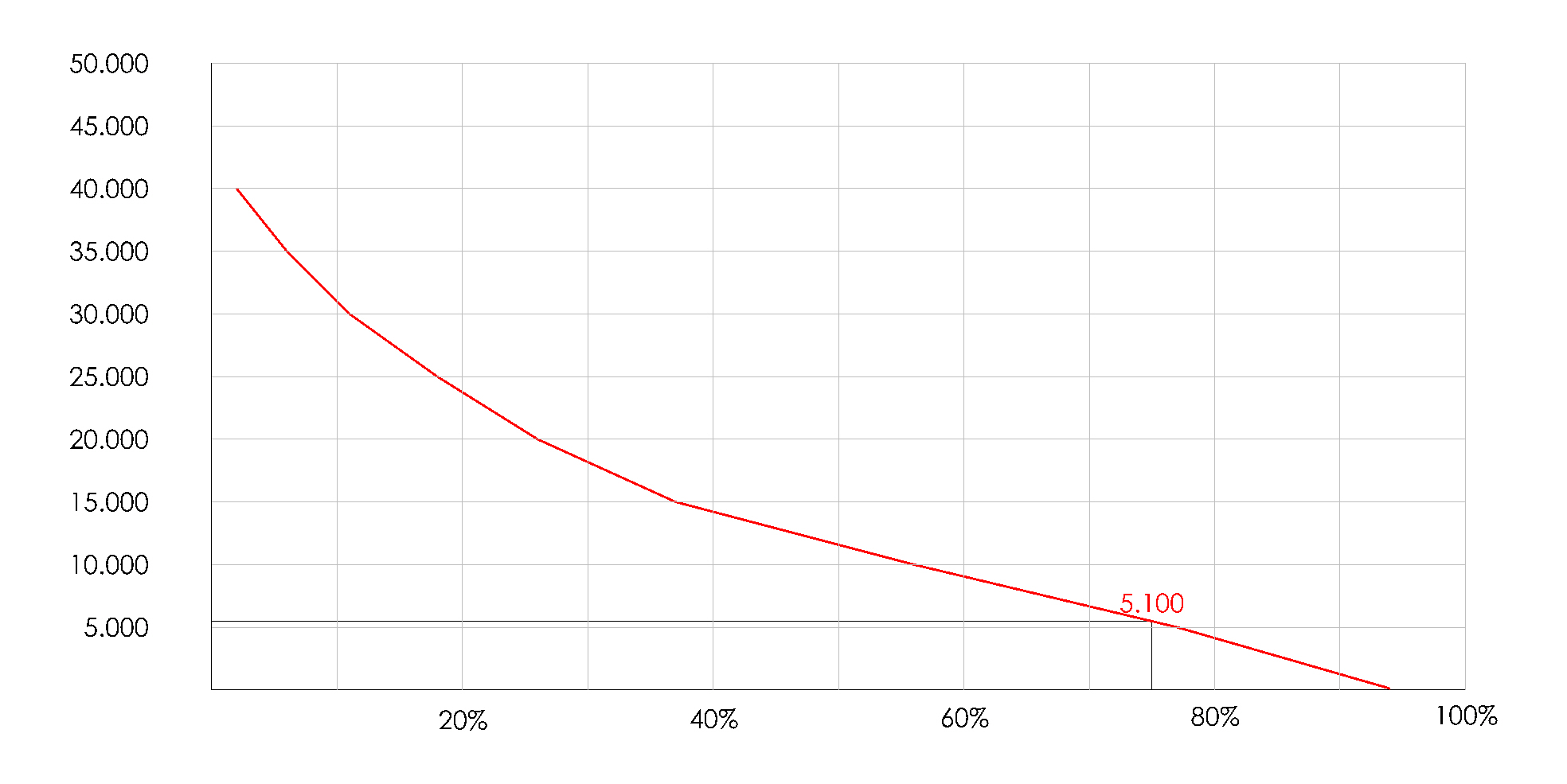

Now, looking at our climate file would seem a dismal affair, as we can see that about half of the time we get 0 lux. But this of course is taking into account all 8.760 hours of a year. This includes nighttime hours. If we narrow it down to just the day hours from 8:00 to 17:00, we can already see some improvement.

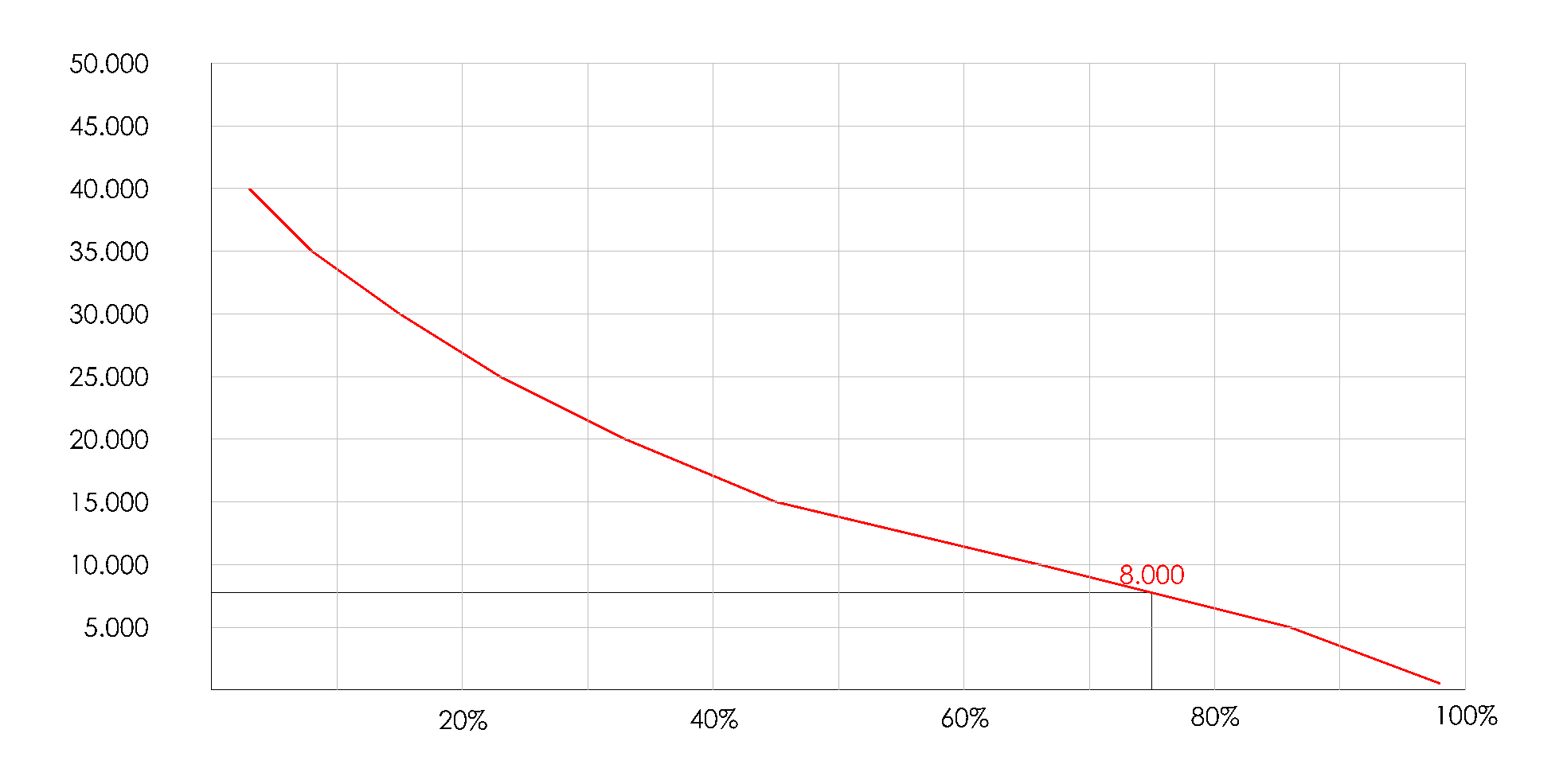

We can now see that from 8:00 to 17:00 we get at least 5.100 lux 75% of the time. This would mean that we would need to have windows big enough to achieve a daylight factor of 1% throughout the room. This is hard, yet achievable.

However, lets say our school hours are from 9:00 to 15:00. We now see that in these 1807 hours we receive as much as 8.000 lux 75% of the time. This means that with a daylight factor of 0.6 we achieve 500 lux 75% of the time from 9 to 15. This meets our target and can be achievable with the right façade design.

3. Why Leveraging time for sustainable design becomes important

It is fair to think that this whole approach can be simply dismissed. After all, if we can meet the requirement from 8:00 to 17:00, we will certainly meet the requirement from 9:00 to 15:00. What is the point of the whole exercise?

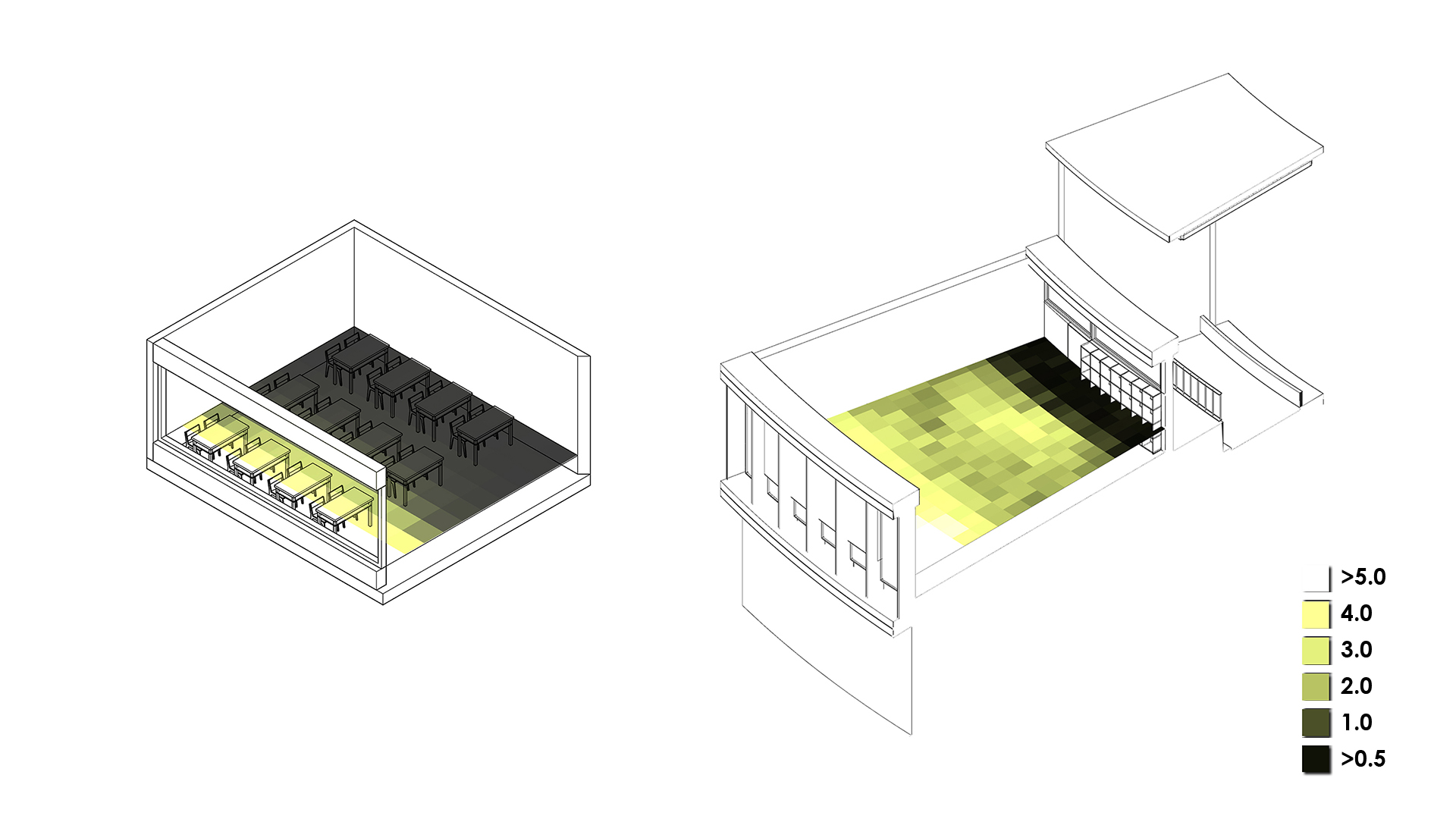

However, the consequences of not undergoing this or a similar approach are many. As an example, consider the shoebox simulation for sidelit classroom. It is illustrated here next to our proposed classroom for our St. Ghislain school extension project.

You can see that in order to achieve the 1% daylight factor required initially we need an enormous window. This kind of fenestration will most certainly bring with it glare issues inside along with overheating problems during the warmer months.

What is even worse is the possibility of discarding the whole idea. If we consider that the requirement is just not achievable, we might not even bother at all. We may still place windows, but now we are not considering daylighting as we have falsely discarded it as unattainable. This kind of uninformed approach may very well not meet the required 0.6 DF.

4. Conclusion

In this article we have discussed the impact time frames may have in sustainable design and how they can be leveraged. We illustrated this with an example set on daylight simulations but the concept may be applied in other aspects as well. Passive solar gains is something often overlooked in Belgium and in a way, rightly so. During the coldest months, solar radiation is too feeble to be of any significance. This is particularly true for the direct component as discussed in our article 3: Belgian climate analysis. However, in some months of our established cool period and the throughout the mild period, direct solar radiation is considerable and is most likely welcome.

The purpose of this article was therefore to link climate with activities and architecture. The idea is to make the most of the resources available, so as to require fewer resources to condition our spaces. This will inevitably result in energy savings while achieving more enjoyable spaces.